Microplastics: The What, Where, Why And Impact

Today's guest blog is authored by Craig Coker is a Senior Editor at BioCycle CONNECT and a Principal at Coker Composting and Consulting near Roanoke VA. The original post can be read here.

Among the organics recycling challenges du jour is the potential presence of microplastics in compost and digestate. Two-part article series starts with an overview and ends with findings of current research. Part I

Food waste disposal bans have been implemented in four states (New York, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Vermont) and diversion requirements are established in six others (California, Oregon, Washington, Connecticut, New Jersey and Maryland). There are also food waste landfill bans and/or diversion policies in a number of communities (San Antonio TX, Boulder CO, Hennepin County MN, Seattle WA and New York City). The oldest of these diversion requirements is in Vermont, which passed its Universal Recycling Law in 2012 and which covers both commercial and residential sources of food wastes.

Over the past 10 years, the organics recycling industry (which includes composting, anaerobic digestion, and diversion to animal feed) has come to recognize that plastics contamination from food packaging is a significant challenge to the implementation and growth of these diversion practices. Plastic packaging is ubiquitous in

the American food distribution system. Many different types of plastics are used in food packaging, as shown in Table 1.

Recovering packaged food wastes for reuse or recycling requires either mechanical depackagers or human labor for source separation, both of which are likely to achieve variable and imperfect separation efficiency (do Carmo Precci Lopes et al., 2019; Edwards et al., 2018). Depackaged and source separated food wastes may contain missorted plastic packaging with varying levels of contamination (Porterfield et al., 2023). Plastic contamination in organics recycling — especially in food waste feedstocks — has led to concerns about microplastics.

What Are Microplastics?

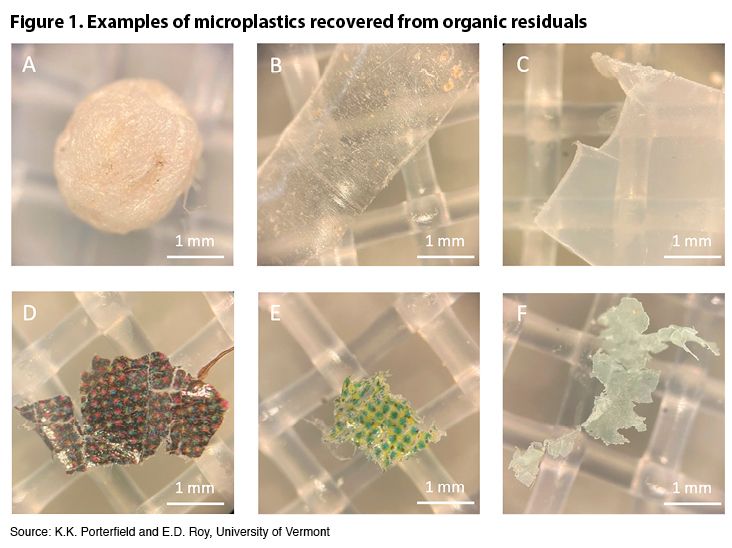

Microplastics (MPs) are small plastic fragments that are less than 5 millimeters (mm) in size — slightly larger than one-eighth inch. A subcategory of microplastics is nanoplastics, synthetic polymers with dimensions ranging from 1 nanometer (nm) to 1 micrometer (μm). For perspective, a compost bacterium is about 1,000 nanometers in size and the width of a single human hair is 20 to 200 μm. Examples of MPs are shown in Figure 1.

There is no consensus on the definition of nano and microplastic particles in relation to human health (Vose, 2022). MPs are directly released to the environment or secondarily derived from plastic disintegration in the environment (Lai, 2022). In a 2021 Spanish study, five polymers represented 94% of the plastic items found in the organic fraction of municipal solid waste: polyethylene, polystyrene, polyester, polypropylene, polyvinyl chloride, and acrylic polymers in order of abundance. Polyethylene was more abundant in films, polystyrene in fragments, polypropylene in filaments, and fibers were dominated by polyester (Edo, 2022).

How Are Microplastics Formed?

MPs can be introduced to agricultural soils through products engineered to be small, such as plastic-coated controlled release fertilizers, treated seeds, and capsule suspension plant protection products. They can be introduced via plastic mulching, contaminated soil amendments, irrigation water, atmospheric deposition, roads and litter (Porterfield et al., 2023 and citations within).

MPs can also be formed during and as a result of food waste depackaging, a separation process. In its simplest form, separation is a binary process, splitting a feed material into two components. These components could be called the extract (or that which you are trying to recover) and the reject (that which you do not want). The objective of a binary materials separator is to split a feed material into two different components by exploiting some difference in the material’s properties.

Separation of materials requires identifying the appropriate characteristic by which separation can be done — or what material property will be exploited to achieve separation. This could be called the “code,” or signal, to tell a machine how to separate materials. The ability of a human or a machine to identify a property’s characteristic and to perform some function, actively or passively, on that material as a result of that information could be called “switching,” or separating the material according to that characteristic (Vesilind, 1984). For example, depackaging commingled food wastes uses density as a code and can use force as a switch to separate packaging, then uses compressive strength (hardness) as a code and pressure as a switch to push organics through an extrusion plate or separator screen.

Depackaging source separated food wastes is very labor-intensive if done by humans. As a result, a number of depackaging equipment systems have come to the U.S. organics recycling market (Coker, 2019; Coker, 2021). The methods used to separate foods from their packages include extrusion (similar to how pasta and ground meat are made), vertical hammermills (force applied against a vertical punch-plate screen), horizontal paddle separators (squeezing the packaging between paddle and containment shell), and centrifugal force separators. There are no data available on which depackaging methods produce MPs or in what quantities, but it is reasonable to assume that machines exerting more force on packaged foods risk higher production of MPs due to shattering of brittle plastics like some high-density polyethylene (HDPE ) and polypropylene.

Health Effects of Microplastics

The research on the health effects of microplastics has focused, to date, on direct exposure. MPs in composts and digestates used as soil amendments are a secondary pathway of exposure, which has not yet been studied to any extent.

Inhalation and ingestion are the two primary routes of exposure to MPs. Inhalation causes physical damage to the lungs and ingestion is thought to have potential impacts on the immune system, liver, energy metabolism and reproduction. There are no comprehensive studies of MPs in the diet, although MPs have been found in seafood/fish, salt, beer, honey, milk, rice, sugar and seaweed (Vose, 2022).

In 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) commissioned a report to evaluate the evidence of risks to human health associated with exposure to nano and microplastic particles (NMP) in drinking water. A key observation is that MPs are ubiquitous in the environment and have been detected in environmental media with direct relevance for human exposure, including air, dust, water, food and beverages.

There is increasing awareness of the occurrence of MPs in air and their implications for human health. Studies of the inhalation of MPs should include consideration of their biokinetics, as their intake depends on their size, shape, density and surface chemistry, which influence their deposition in the alveolar regions of the lungs. Better characterization is needed of the properties of MPs in air, such as the fractions that contribute to airborne particulate matter and their absolute concentrations. The current lack of such data limits characterization and quantification of the impact of human inhalation of MPs.

Ingestion of MP has been reported in a variety of foods and beverages. An assessment of overall human exposure to MPs is complicated by the limited availability of data on the occurrence of MPs measuring <10 μm in water, food and beverages. Observations from particle and fiber toxicology indicate that particles <10 μm are probably taken up biologically. Most of the available studies on the occurrence of MPs in water, food and beverages reported particles measuring >10 μm, which are unlikely to be absorbed or taken up.

The WHO assessed the quality, reliability and relevance of data on both exposure and effects for their possible contribution to a risk assessment of MPs. The assessment scores indicated that the available data are of only very limited use. Several shortcomings were identified, the most important of which was the heterogeneity of the methods used. It is recommended that standard methods be developed and adopted to ensure that the research community can reduce uncertainties, strengthen overall scientific understanding and provide more robust data for assessing the risks of human exposure to NMPs (WHO, 2022).

Environmental Effects of Microplastics

MPs are categorized as emerging persistent pollutants that occur widely in various ecosystems. MP measurements reported in the literature are 10’s to 1,000’s of particles per dry kilogram of agricultural soils, similar to levels found in composts and digestates (Porterfield et al., 2023). Microplastics in soils have been found to increase soil aeration, water repellence and porosity but to decrease soil bulk density and aggregate sizes (e.g., de Souza Machado et al., 2018b, 2019; Kim et al., 2021; Qi et al., 2020).

MPs’ impacts on terrestrial plants (particularly crops) are poorly understood. Given the persistence and widespread distribution of MPs in the soil, they have potential impacts on terrestrial plants (Wang et al., 2022). Due to their small size and high adsorption capacity, MPs can adhere to the surfaces of seeds and roots, and thus inhibit seed germination, root elongation, and absorption of water and nutrients, and ultimately inhibit plant growth. MPs, especially nanoplastics, can be absorbed by roots, and be moved to stems, leaves, and fruits. The adherence and accumulation of MPs can induce oxidative stress, a complex chemical and physiological phenomenon that occurs in higher plants (vascular) and develops as a result of overproduction and accumulation of reactive oxygen species. They also can induce toxicity to plant cells and to genetic material in plants, leading to a series of changes in plant growth, mineral nutrition, photosynthesis, toxic accumulation, and metabolites in plants tissues. Overall, the phytotoxicity of MPs varies dependent on their polymer type, size, dose and shape, plant tolerance, and exposure conditions. The accumulation of MPs and subsequent damage in plants may further affect crop productivity, and food safety and quality, causing potential health risks (Wang et al., 2022).

Soil microorganisms can be affected by MPs. There are effects on species dominance, diversity and richness reported in the literature (e.g., Blöcker et al., 2020; Fei et al., 2020; Ren et al., 2020) and MPs have been found to cause oxidative stress and abnormal gene expression in earthworms (which can consume and transport MPs) (Cheng et al., 2020).

Even compostable plastics can be a source of MPs. Not all certified compostable packaging fully composts in all facilities due to variability in the technologies and processes used at each facility (USEPA, 2021). The European compostable plastics standard (EN 13432) defines a material as compostable, if 90% (by weight) of the material is fragmented (disintegrated) into particles <2 mm, i.e., below the limit at which particles “count,” after 12 weeks of standardized composting and fully mineralized by 90% within 6 months. The remaining 10% may be transformed into biomass or simply be fragmented into microplastic (Steiner, 2022).

Disclaimer: Guest blogs represent the opinion of the writers and may not reflect the policy or position of the Northeast Recycling Council, Inc.

Share Post